I started to research interactive documentaries back in 2013 when I was living in Italy, because this hybrid form of storytelling matched my interest in digital narratives and audience engagement. As soon as I moved to London I looked for people interested in the topic and immediately found out that one of the leading researchers in the field, Sandra Gaudenzi, was running a Meetup called London’s Interactive Factual Narrative.

The name speaks for itself: it’s not about fiction, and it showcases state of the art technology applied to storytelling. Last year I had a preview of Nonny de la Peña’s Project Syria and Ulrich Fischer’s MemoWays, a new platform to tell personalised stories. Now, thanks to the interest of the University of Westminster that is hosting this edition, Sandra kicked off 2015 by providing a new place for this eclectic community made of filmmakers, coders, gamers, researchers and people just passionate about interactive stories.

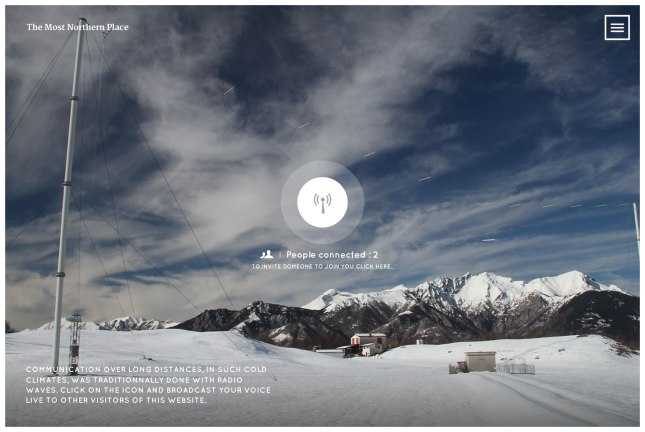

The first event of this year was actually a relished surprise, as she organised a discussion around “strategic passion” for creative people (in short, how to invite professionals to adopt a story and give some of their time to grow a project together). I already knew the speaker she invited, as I had got in touch with Anrick Bregman for my series of posts about his interactive documentary, The Most Northern Place.

I thought I knew the project quite well but I have to admit that I was struck by the passion Anrick showed on stage. It was something that I hadn’t experienced before, given the fact that my interview “took place” via email. In a way, I was re-discovering The Most Northern Place through a different (I would say more emotional) approach. Anrick openly shared his mistakes, the trials and errors, the quest for the perfect design and platform, technical issues, what worked and what did not. In some respects, his talk and the Q & A that followed were themselves a form of interactive storytelling (by the way, it was here that the crisps of the title came centre stage, during the break).

I soon realised that his way of speaking was really close to the pace of his documentary. It was a continuous, almost cuddly flow that mirrored what he was reminding us of in his slides: “Don’t rush. It’s not a race.” Anrick is not someone who shows off (although he could, given his CV). He went through the different stages of his process (“Develop the Idea”, “Imagine the Experience” and “Build the Team”), and focused on some key questions that everyone planning any audiovisual narrative should ask themselves: What is your story? What does your viewer do? Also, consider how the interactivity will affect the perception of the story itself.

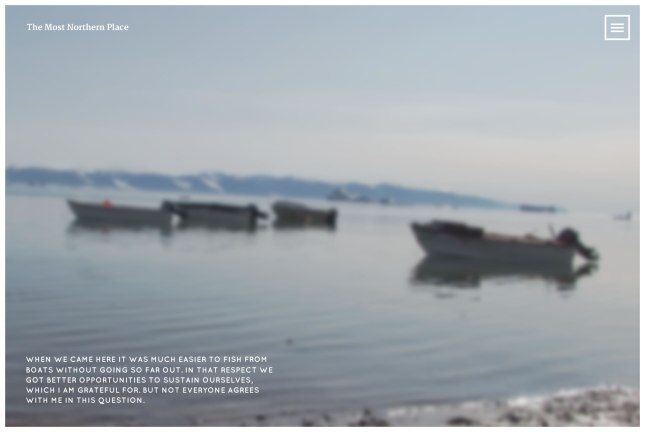

I leave you with one of his final remarks, something that usually is at the bottom of the list of a creative mind, but should instead be on top of it. “Do what you think is beautiful, or meaningful, or good. Because you’re the one that has to live with it.” This is even truer if you spend four years of your life creating it. I think that with The Most Northern Place Anrick achieved all of this, but you don’t have to trust me. You can see for yourself by watching it and exploring the true story of Thule.